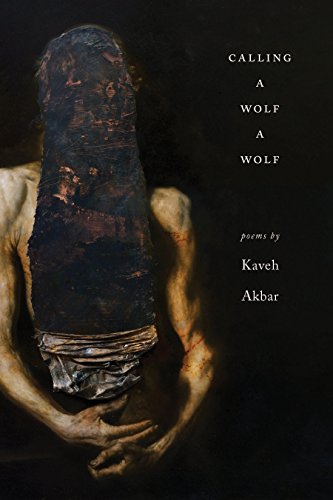

(Farsi is read right to left, a reminder that our notion of backwardness is always arbitrary.) The six enigmatic poems that share the book’s title are studded with periods that keep interrupting the speaker midsentence, as though his hurtling train of thought required speed bumps. One poem is printed backward, forcing us to either hold it up to a mirror or patiently decode it letter by letter. Flip through this book and you’ll notice formal and stylistic strategies that play at the edges of decipherability. Sometimes the lack of clarity is literal. In “the absence of cloud-parting, trumpet-blaring clarity,” these poems ask what meaning can be found-or made-through partial revelation, in a world so often defined by misunderstandings: with others, with God, with ourselves. It may be both good and bad fortune, then, that no grand truth will be elucidated for the poet: “Gabriel isn’t coming for you,” Akbar tells himself. In Akbar’s retelling, this gift of knowledge isn’t benevolently bestowed it’s thrust upon the recipient without his consent, the angel “squeezing out the air of protest, the air of doubt, crushing it out of his crushable human body.” Language can illuminate the world, but it can also destroy a self. “The Miracle,” written in short, parable-like paragraphs, opens with a story from the life of Muhammad, in which the Prophet, then an illiterate merchant, is visited by the angel Gabriel, commanded to “read,” and given his first revelation. In his most recent collection, “ Pilgrim Bell” (Graywolf), words assume physical, palpable form-as reverberations in the mouth and ear-but can just as easily take on a spectral aura, reminding us of worlds and selves no longer within reach. Poetry requires the opposite of such carelessness, and Akbar is exquisitely sensitive to how language can function as both presence and absence. In a poem called “Do You Speak Persian?,” Akbar writes, “I have been so careless with the words I already have. / / I don’t remember how to say home / in my first language, or lonely, or light.” Akbar, who was born in Iran, arrived in the United States when he was two, a transition that imparted another lesson in linguistic gain and loss: while he picked up English, Farsi began to fade. He could inhabit the lyric beauty of the words, he discovered, even without grasping their meaning.

Mimicking those incantatory sounds, he briefly embodied a foreign tongue.

When the poet Kaveh Akbar was a young child, his father taught him to recite Muslim prayers in Arabic, a language Akbar didn’t understand, and which his family spoke only during worship.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)